German POWs in Peabody, Kansas: 1943-1946

Melvin D. Epp, Ph.D.

Contemporary history books often minimize the fact that during World War II, the United States incarcerated prisoners of war (POWs) in camps within the continental U.S. As the Unites States military in North Africa succeeded in capturing German soldiers, as well as a few Italian soldiers, the numbers of POWs began to multiply and with time more than 100,000 arrived in the U.S. Ships that took war supplies including food to Europe were used to transport prisoners from Europe to America, rather than make the return trip with an empty ship. It was thought, that maintaining these prisoners in the U.S. would be less expensive and logistically more effective, additionally they could be used as a labor replacement as America’s sons were fighting in Europe. With time there were 666 camps (155 main camps and 511 branch camps) and of these 16 camps were in Kansas. The smaller branch camps were located where there was employment available and where the POWs could impact labor shortages.

It has also been suggested that bringing the POWs to the United States was a secret program designed to change the men’s minds without them perceiving the change. Judith Gansberg has suggested that this was intended as a reeducation program for the German POWs in captivity and designed to do more than just hold the men captive. The reeducation program provided a vanguard for the Americanization of postwar Germany.

There was also the feeling that we should treat the POWs as we wanted the European nations to treat the American POWs—the Golden Rule concept. If the U.S. treated POWs badly, the Axis powers would have an excuse to treat American POWs badly.

A POW branch tent camp was set up in Peabody on September 11, 1943 just south of town at an old creamery and then relocated to the 1919 Eyestone Building at 122 West 2nd Street on November 28, 1943 after the chill of winter set in. The building was surrounded by a high wire fence. The POWs were housed in rooms on the ground level while the guards lived on the second floor. The number of POWs fluctuated from 150 to 200 prisoners during the war years. The POWs that came to Peabody were men who had volunteered to do farm labor.

Along with the POWs, 58 U.S. guards, members of the 480th Military Police Escort Guard Company, were also assigned to the Peabody camp.

Local farmers and businesses could hire these POWs by the day. Many farmers in the Frederic Remington Area Historical Society (FRAHS) area utilized this inexpensive man-power. The wages to the government for using POW labor was 35 to 45 cents per hour and the government used this to offset the cost of keeping POWs. The wages were consistent with local wage scales. For the POW, he received 80 cents per day; of this amount he was given half in canteen script and the rest was put in an account that he received at the end of the war.

POW labor was accompanied by fairly strict guidelines. Farmers picking up prisoners were asked to arrive no later than 7:45 a.m. The POWs could work from 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. To transport the prisoners, farmers initially were asked to put racks on their truck beds so that soldiers could not jump out. Flatbed trucks were not permitted for hauling prisoners; farmers were instructed to drive safely and at a reasonable speed. Farmers were to give these laborer a ten-minute break hourly, as well as have water available at all times. One meal per shift was to be provided unless the location of the work was within a two-mile radius of the camp; in that case the POWs were to be brought back to camp for their noon meal. The POWs were allowed to do various types of farm work except they were not to be allowed to drive trucks or operate farm machinery. They were also forbidden to hoe weeds in tall green corn; this was to prevent heat exhaustion in windless humid corn, and lack of visibility by the ever-present guards. While working, the farmer or a farm supervisor was to work directly with the prisoners. Also, conversing with the prisoners was prohibited, especially conversations involving politics or the war. No one was allowed to stand or walk between the guards and the prisoners. Guards were to accompany the POWs constantly.

Communication with the POWs who came to Peabody was enhanced because many farmers in the FRAHS area were of German decent, having immigrated to the U.S. only 50 to 70 years earlier. The German or Low German languages were still the language of choice in many homes. Additionally, many of the farmers were culturally Mennonite whose practice of pacifism promoted the attitude of healing wounds rather than inflicting wounds.

Early-on the strict military guidelines were followed. The POWs were picked up in a stock truck enclosed with racks. Neighboring farmers would truck-pool in picking up the day laborers with their guards. As a guard would climb up into the truck, the protocol was that he gave his gun to another guard on the ground; after the first guard was in the truck, the guard on the ground gave the guard on the truck his gun again. The Americans were thankful for the guards, thinking they were kept safe from the POWs, while the POWs considered the guards as safety shields from the Americans. Remarkably, most of the POWs at Peabody were very humane and non-political, simple young men caught up as international pawns in world affairs.

One of the stated guidelines was that the POWs on work assignments were to be served one meal a day. My mother declared that these men could not work on an empty stomach, so she made egg sandwiches and filled a large coffee pot with hot coffee and sent my older siblings to the field; my mother insisted that this was not a meal, it simply was a coffee break. Other farmwives likewise followed this procedure because traditionally the labor intensive farm work in German fashion required a breakfast at daybreak, a mid-morning snack, the noon meal, an afternoon snack, and then supper after the sun set.

During the first few days of using POWs, the POWs expected the noon meal to be served to them outside using tin cups. Instead, many farm wives within the FRAHS area set up their dining room tables to serve the noon meal. When the women invited the men to the indoor table using the German language, many POWs were brought to tears. They just were not emotionally prepared for such civil hospitality. The guards were also invited to the table and early-on they would bring their guns with the attached bayonets with them to the table. As time passed, the tension between the POWs and their U.S. guards dissipated. The hospitality of the Mennonite homes and community extended equally to both and the guards began to leave their guns on the porch during lunch.

When my aunt Maria Wiebe invited the POWs to her dining table, the men looked around the room, and were able to read German wall plaques and mottos on the wall. Apparently, the emphasis on love and respect for mankind solicited an emphatic response, “But we did not kill anyone.”

Marian Franz relates that after the guards and POWs were more relaxed, one hot afternoon a guard was napping under the shady trees along the creek, while the POWs were working in the field with the farmer. The POWs suddenly notices a fast-approaching jeep loaded with military superiors, coming to inspect the guard on duty. Several prisoners rushed to awaken the guard who regained his watchful post. After stiff salutes and the clatter of weapons inspection there was intense conversation. Apparently satisfied that the prisoners would not escape under such careful watch, the officers boarded their jeep and disappeared as quickly as they had arrived. The silent tension of the field became raucous laughter as the guards and POWs alike enjoyed the success in dealing with that close call.

Some of the recollections of my siblings Phebe and Albert include:

“I do remember shocking wheat side by side with the prisoners, and they were good steady workers.

“One POW with curly hair sometimes sat at the piano and played beautiful pieces from some of the noted German composers. He was a gifted musician.

“At the dinner table the men displayed hearty appetites. I do recall them commenting on the dish of corn. They questioned whether corn was not better suited for feeding livestock, the cattle and pigs.

“I recall one prisoner saying that if America would release them to the French government, he would commit suicide. He apparently felt the French were cruel heartless people.

“Frequently, our father would request to have one POW, Willie Henrici, come to our farm. He spoke the Prussian German dialect like we did. He was about 40 years old. He had been a hotel owner and he did not know whether his wife and daughter were still alive. While at our farm he enjoyed playing with my sister who was 3-6 years old during that time. He repeatedly invited my parents to visit him in Germany whenever he would get back. When the POWs were released and sent back to Germany, we got word that Willie had found his family. The first Christmas that he was back in Germany, he sent my sister Justina a doll. My parents continued to exchange Christmas cards with him yearly. In 1962, when my parents went to Germany, they connected with the Henrici family, visiting Willie, his wife Lenna and daughter Helga in their home. It was a happy reunion. Helga continued to send Christmas cards to my sisters after my parents died and repeatedly expressed gratitude for our kindness to her father. The last card was received in 2014 and in translation read, ‘For your extended family, I wish for you a happy Christmas and for the new year everything, everything good. With loving greetings.’”

On February 3, 2014, after Mark Schock gave a lecture at our FRAHS meeting entitled “Prisoners of War in Kansas 1943-1946” (This lecture is available from FRAHS on a DVD), the audience was asked to share their recollections.

Walter Penner told the story that at the end of the day, the POWs needed to be back in Peabody by 6:00 p.m. Farm work, of course, generally continued until dark, ca. 9:00 p.m, so his father arranged for his mother to take the POWs back to Peabody. Frieda Penner drove the car and one of the POWs held her toddler in his lap sitting in the front seat. Frieda was very comfortable with this arrangement—they all spoke German and were like friends. When they got to Peabody, there was a reporter from the Wichita Beacon observing the return of the POW workforce. That evening the reporter wrote an article “Nazi War Prisoners at Peabody ‘Coddled’” that was published the next day on August 30, 1944. This resulted in new government directives that farm wives were not allowed to chauffeur POWs.

Walter also mentioned in the Emmaus Mennonite Church’s Emmaus Echoes, October 2013, that he vividly remembered seeing a guard give his gun to the POW in the passenger seat, so that he could drive a car from the field to the farm.

Wilbert Wiebe recalled a similar situation where he saw a guard ask a POW to hold his gun so that the guard could climb to the top of the silo and view the countryside.

My recollection is that I was only 3 or 4 years old when my father had POWs on the farm. I was learning to talk and said something in German to a POW. The POW got down on one knee and gently explained the grammatical error in the German that I has just spoken. I had no clue what he meant, but my older brothers just roared with laughter.

There are still artifacts within the community, which POWs either crafted for their employers and friends while in Peabody, or sent after they were back in Germany. I have already mentioned my sister receiving a German doll as a Christmas present. The Ed Regiers had a POW who was great in woodworking and left a lawn chair set and a wooden suitcase, which Daryl and Shari Regier have at the farm Orchard House. Additionally, they too have Christmas cards sent from Germany. One of the POWs working at the Jacob Thiessen farm, drew a picture of the Emmaus Church. Photos of these artifacts follow.

POW Willie Henrici in 1940

The doll that Willie Henrici sent to my sister Justina for Christmas in 1947. The doll says, “Mama.” It is now in the collections of one of Justina’s daughters.

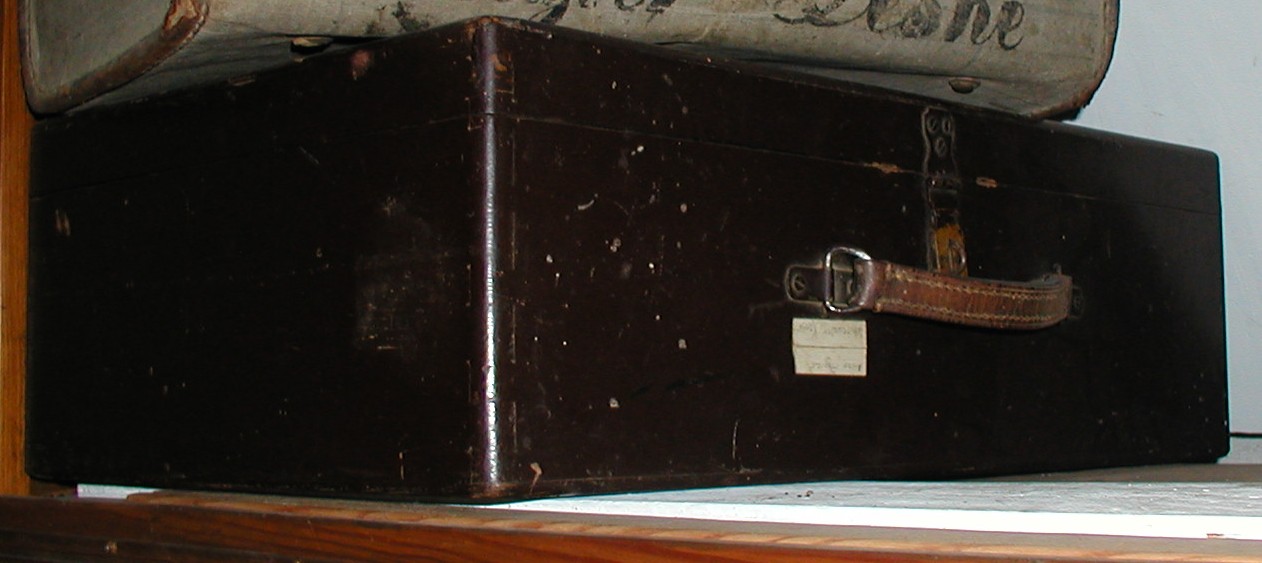

Artifacts created by a POW and retained by Daryl and Shari Regier

The wooden suitcase and a lawn set that had three chairs and a round table.

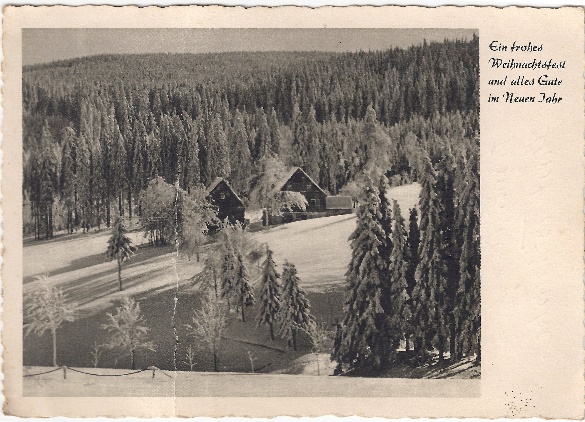

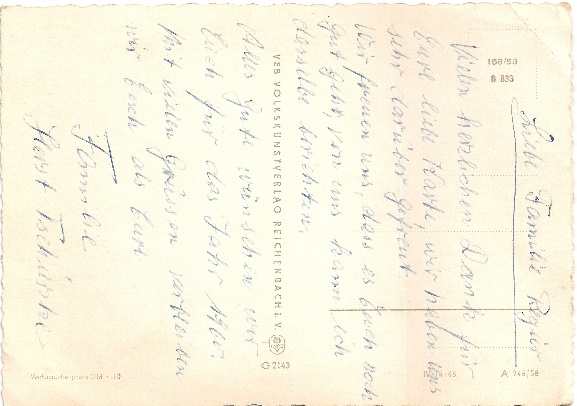

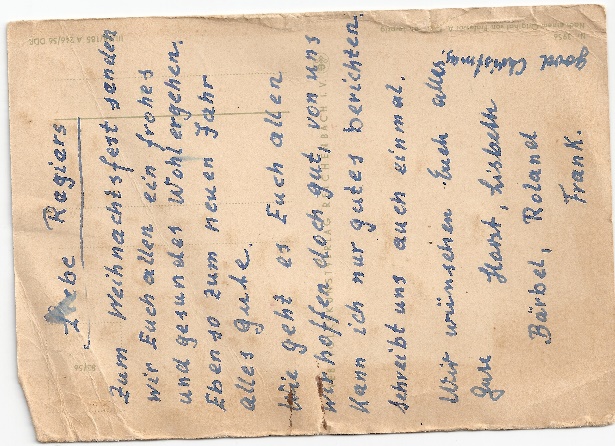

Christmas cards sent to the Ed Regier family

Dear Regier Family,

Many heartfelt thanks

for your lovely card,

we were very pleased

with it. We are happy

that things are going

well for you; I can

report the same for

us. We extend all

good wished to you for

the year, 1960. With

many greetings we

remain also as your

family.

Horst Tschurske

Dear Regiers,

For the Christmas holidays

we are sending you all a

happy and a healthy wish

for well-being. Also for

the new year, everything

good. How is everything

going for you? Yes, we

hope good, from us I can

only report good. Write

us also sometime. We

wish for you everything

good, Good Christmas.

Horst, Lisbeth

Bärbel, Roland

Frank

![C:\Users\user\Pictures\My Pictures\Manuscript photos\Emmaus Church\Emmaus_1945[1].jpg](https://fredericremingtonareahistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/c-users-user-pictures-my-pictures-manuscript-phot-3.jpeg)

In 1945, during the noon break, Herman Pfӓtzner, a World War II German prisoner, sat on the cement slab under the windmill at the Jake Thiessen farm, sketching this picture of the Emmaus Mennonite Church, Whitewater, KS. One month later, Herman Pfӓtzner painted this picture at the prison camp in Peabody, KS.

Reference Sources

Epp, Marie Harder. Lest We Forget. Whitewater, KS: n.p., 1992, p. 68.

Epp, Melvin D. The Petals of a Kansas Sunflower: A Mennonite Diaspora. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2012, p. 373.

Epp, Melvin D. For the Children: Pursuing Religious and Political Freedoms. Newton, KS: self-published, 2015, p. 197.

Franz, Marian Claassen. She Has Done a Good Thing: Mennonite Women Leaders Tell Their Stories. Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press (MennonMedia), 1999.

Gansberg, Judith M. Stalag: U.S.A. The Remarkable Story of German POWS in America. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1977.

Krammer, Arnold. Nazi Prisoners of War in America. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Scarborough House, 1979.

May, Lowell A. Camp Concordia: German POWs in the Midwest. Manhattan, KS: Sunflower University Press, 1995.

May, Lowell A. and Mark P. Schock. Prisoners of War in Kansas, 1943-1946. Manhattan, KS: KS Publishing, Inc., 2007.

Miller, Joseph S. “German POWs at Peabody and Concordia, Kansas, during World War II.” North Newton, KS: n.p. Research Paper in Mennonite Library & Archives, 1987.

Rodenberg, Ethan. “German Prisoners of War in Peabody, Kansas: Success of the Labor Program.” North Newton, KS: n.p. Research Paper in Mennonite Library & Archives, 2015.